Rally For RRHA Residents

Today Leaders of the New South (LNS)’s Community Council for Housing assembled with Richmonders from across the city in support of public housing residents who have lived without sufficient heat for over a year. LNS leadership Omari al-Qadaffi has done a tremendous amount to chronicle the last week in the lives of Richmond Redevelopment Housing Authority (RRHA) tenants. He has identified heat deficits in major housing developments across the city. The testimony of residents is incredibly moving: families sleeping in layers of coats and blankets, individuals with targeted health needs who are unable to seek out shelter elsewhere,* thick sheets of ice formed on interior walls, families heating their homes with their ovens, and residents given space heaters by RRHA only to be charged for electrical use overages.

The failure of RRHA to provide residents heat is only the latest in a much longer pattern documented by public housing advocates like al-Qadaffi, Lillie A. Estes, and Arthur Burton. It’s a pattern of community exclusion in a broader political landscape where the city has opted for privatization in lieu of funded democratic governance of our public resources. As Tom Nash reported in Style last summer:

For years, the housing authority has discussed decentralizing poverty by breaking up the massive housing-block developments, well before Somanath, formerly head of the Richmond Better Housing Coalition, came out of retirement. Gilpin Court resident Lillie A. Estes, the organizer behind tenant advocacy group Residents of Public Housing in Richmond Against Mass Evictions, known by the moniker Rephrame, and a 2016 mayoral candidate, says the most recent push is occurring in circles that do not include public housing residents.

“The challenge with decentralizing poverty lies in laying a structure when the people involved aren’t there,” Estes says. “What [the authority] should be doing is fostering inclusion for people to speak for themselves.”

The city seems immune to the notion that tenants should contribute to the governance of their own housing. For over a year tenants have demanded repairs to the aging heating system. For over a year the city has offered space heaters and held off on repairs. Finally this week the city partnered with a private hotel to relocate residents until the cold passes: an insufficient solution that would leave tenants without kitchens, transportation, or access to the communities in which they live. Despite repeated statements from residential and community leadership that hotels would not meet the needs of residents, the city feigned surprise when many residents refused to relocate. Also apparently immune to any sense of decency, RRHA demanded residents who remain sign waivers releasing RRHA of responsibility for tenant safety in freezing accommodations.

Hotels or Housing? The question perfectly encapsulates the city’s approach to public need: Richmond has entered a seemingly endless cycle in which community leadership demands public and democratic governance of public goods, to which city government responds with solutions developed by private interests, custom designed to meet the needs of Richmond’s disproportionately powerful developer class. Art Burton beautifully outlined the city’s failure to care for its citizens in its mad scramble to please privatized development:

We have pushed back against housing policies that either gentrify our communities or leave them blighted. Education policies fail our children and educate them in crumbling buildings. Transportation plans that force us to walk farther, wait longer, and leave us 3 miles from all the places that we need to be. There is no economic development plan for black people that addresses systemic economic inequality. We penned our hopes on an “Office of Community Wealth Building” that has been implementing policies penned by white neo liberals who continue to funnel money to the white housing development class, their friends and cronies in the mistaken belief that only through paternalism can black people find relief.

Mixed use development and poverty de-concentration strategies further ensure that ownership and empowerment of black people will never occur on any large scale manner. Of the 80,000 black and brown people who live in poverty in this city; why is the focus on public housing, which constitutes only ¼ of the people in poverty only serves to forward the goals of the corporate class and those goals are as follows:

Elimination of Black political power in the city

The removal of federal protection that poor black people are under and confiscation of land.

The continued transfer of wealth from blacks to white developers in the form of housing vouchers and control of city dollars.

Art goes on to say, “In the ‘mixed use development’ the only salvation for blacks comes from living with white people or turning over the control of our communities to the corporate class.” His analysis is backed by research. There is no evidence poverty deconcentration alleviates poverty. There is evidence it is insufficient to intervene in poverty, it disrupts communities, reduces the access of low-income individuals to much-needed public services, and fuels gentrification. Why do cities favor this method? In many places, as in Richmond, developers have a disproportionate hold over city leadership. We live in an era where starvation of public resources provides a perfect landscape for private interests to offer “solutions” for profit.

We live in an era of private intervention in public need. Conservative policy makers starve schools, and private interests offer profitable solutions to the resulting devastation. In housing and transportation policy makers disinvest in public services, focusing instead on gentrification as “wealth-building.” When circumstances become desperate, developers argue in favor of pushing those residents into the private sector. My own work centers primarily in criminal justice reform and public schools -- areas where housing has a tremendous impact. In Richmond today I see many points of overlap in the city’s approach to “fixing” housing and “fixing” schools. In both sectors community leadership has demanded investment and shared governance. In both sectors the city has responded with proposals to shut down services and relocate recipients. It’s no coincidence that the mayor proposes to close schools at the same time that he plans to convert public housing into “mixed-income development.” Private interests have governed our city for too long.**

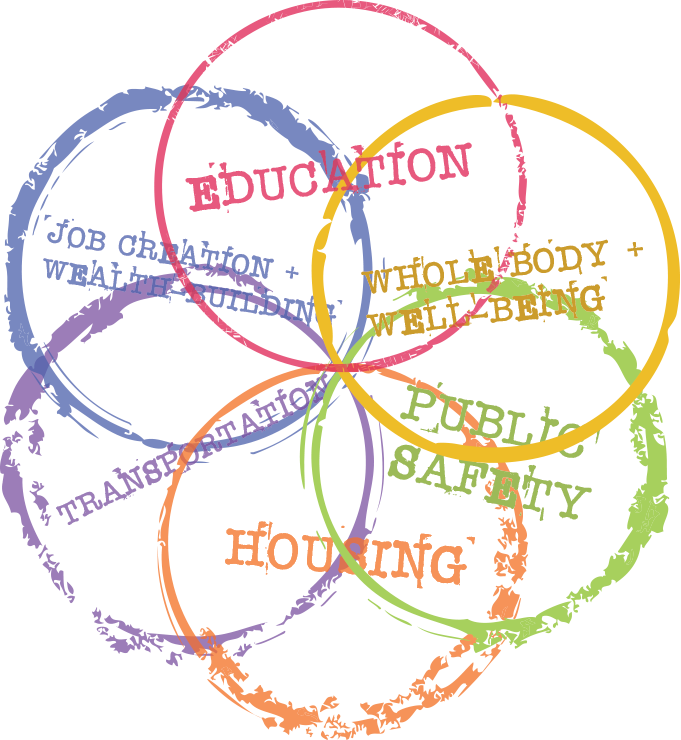

Today was a milestone. Public housing advocates are amplifying public voices in a city where corporate interests have been given a megaphone. When residents like Burton, Estes, and al-Qadaffi fight on behalf of public housing residents, they set the stage for a broader fight in which all of us have a stake. Richmonders have a right to democracy in their city. It is our city, these schools are our schools, and our communities have a right to robust public services with equal access to public governance. The only solution to problems created by economic starvation is through community investment: fair wages, job creation, accessible food and transportation, and robust school funding. We can have all of these when we wrest control of our city from the hands of its incredibly small but powerful developer class.

* For more direct reporting on resident experience you can see Omari’s facebook page, or read coverage by Michael Paul Williams in the Richmond Times Dispatch.

**There are so many examples it would break my heart and my server to list them all here, but the example that currently interests me the most a 2007 letter signed by what has become known as the “gang of 26” arguing against a democratically elected school boardand in favor of a board selected privately by local business leaders. Consider that a moment: Richmond business leaders feel so entitled to run our city that they demanded the elimination of democratic governance of schools in favor of private management.