Disrupting the Status Quo for a Better Future in RVA

By Adrienne Cole Johnson, Alfred Durham, Alycia Comer-Wright, and Jacqueline Johnson

Published in the Richmond Times-Dispatch on October 6, 2018

The Community Justice Film Series (CJFS) has questioned what justice looks like in Richmond by viewing — through the lens of cinematic exploration — documentaries from across the nation. Because the films culminated with thought-provoking questions and discussions, viewers were often left to ponder what is next and how to move forward. As the CJFS evolves, we transition into the meaningful work of the Community Justice Network (CJN), serving as a direct result of the work that began in 2016. To plan its operations — and ultimately its success — in a co-creative and inclusive manner, the CJN members must view ourselves as we view the network’s name: “disruption innovation” in social justice. Disruption comes from a hunger for a better life. Seeing the network through a disruptive lens ensures the community can view its operations as accessible, affordable, new, dynamic, and actionable. It encourages the community to adopt foundational principles with the collective talents and strengths of the group at the forefront.

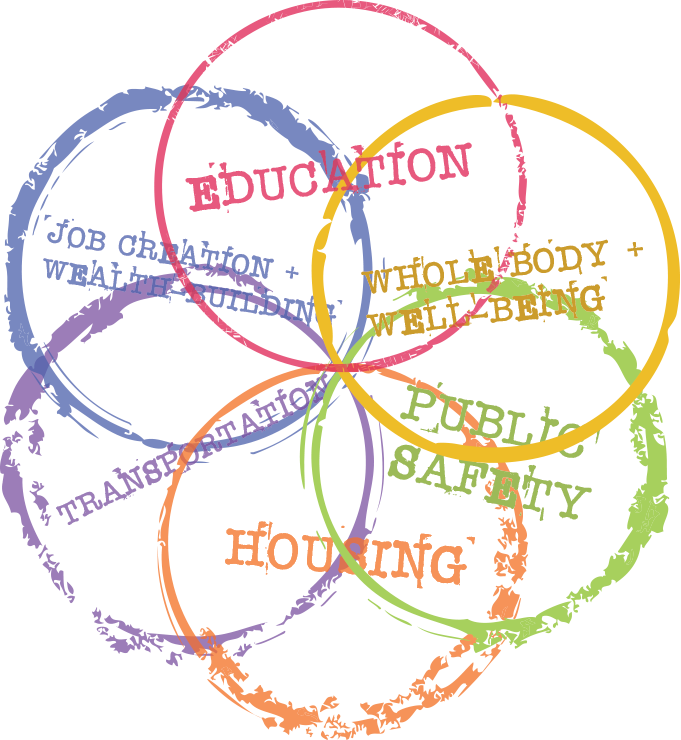

But why “community justice” and not just justice? Because understanding the context of community as we create and support equitable solutions and initiatives truly makes a difference in approach. It views issues such as crime, housing, education, and employment in a broader context, and strives to find a solution that leaves the community stronger and better — on its own terms.

Generally, we can define the community as groups and individuals who will not only commit to supporting a common agenda but also to working together toward positive action items. The CJN community comprises those whose bodies and daily activities are most affected by the policies and laws that govern them — and therefore are decision-makers through democratic processes. In clearly defining the community, together we can facilitate dialogue and refine our work, support implementation by aligning our goals and strategies, continue engagement, conduct advocacy, and establish a process to learn and improve.

As much progress as we have made, that much work is still ahead. Today represents some of the most challenging times regarding justice-related issues, so there is no question that the work of the CJN is relevant.

Consider the relationship between law enforcement and the communities which it serves. A term that has been used in policing for several decades now is community policing. In 2005, Chief Rodney Monroe changed the model of community policing for the police department. While this model of community engagement has been very successful for a number of communities in our city, we still struggle to bridge the gaps of communication, respect, and trust that exist in a number of our most challenging communities.

Community policing differs from the traditional model in both the process and the desired outcome. The process emphasizes full involvement of the key involved parties, such as victim and offender.

This addresses the history of conflict that is oftentimes evident and relevant. Then there are the secondary victims of crimes as well — notably, the communities that have been disrupted. In other cities across the country, criminal justice systems are employing the community justice model. We have a great opportunity in Richmond to enhance our approach to this, and it will take the disruptive innovation approach of groups such as the CJN to do this effectively.

Educational equity and justice is another poignant area of opportunity for our region. Where the CJFS began questioning what it means to be educated and what education looks like in underserved communities, the CJN has the opportunity to act on the conversation with tangible initiatives and impact. One could easily visualize a larger, more comprehensive leadership board — consisting of students, parents, teachers, community elders, business owners, and spiritual leaders — that would add diverse perspectives to the conversation. Incorporating and weaving the talents of the community would undoubtedly be beneficial to our schools and educational centers.

To work in true collaboration, CJN must think systemically to design and implement change processes to achieve the impact that will require various sectors, organizations, and levels of government to work in tandem. We must affect people and policy alike. Those whose daily lived experiences are in urgent need of justice must be involved in final decision-making.

Our excitement for the future comes from a burning desire to disrupt the traditional ways of working in our effort to employ an innovative approach to collaboration and collective work. If you are interested in getting involved, please connect with the CJN via our website: www.communityjusticenetwork.com. We are actively retooling our next steps and we welcome the varied voices of our region to move us along the path of community justice.

———

Adrienne Cole Johnson, MSW, is a social justice professional focused on creative approaches to change who has worked in the areas of engagement, education, entrepreneurship, and politics for the past 20 years.

Alfred Durham is the chief of police for the Richmond Police Department and has served in law enforcement for more than 30 years.

Alycia Comer-Wright, M.Ed, is a former public educator turned homeschool mom. She runs a local homeschool cooperative for families of color and serves as director of Intersectional Activism for Together We Will USA.

Jacqueline Johnson is a training and development consultant specializing in workplace diversity and inclusion and community engagement strategy. She primarily works with mission-driven and place-based organizations.